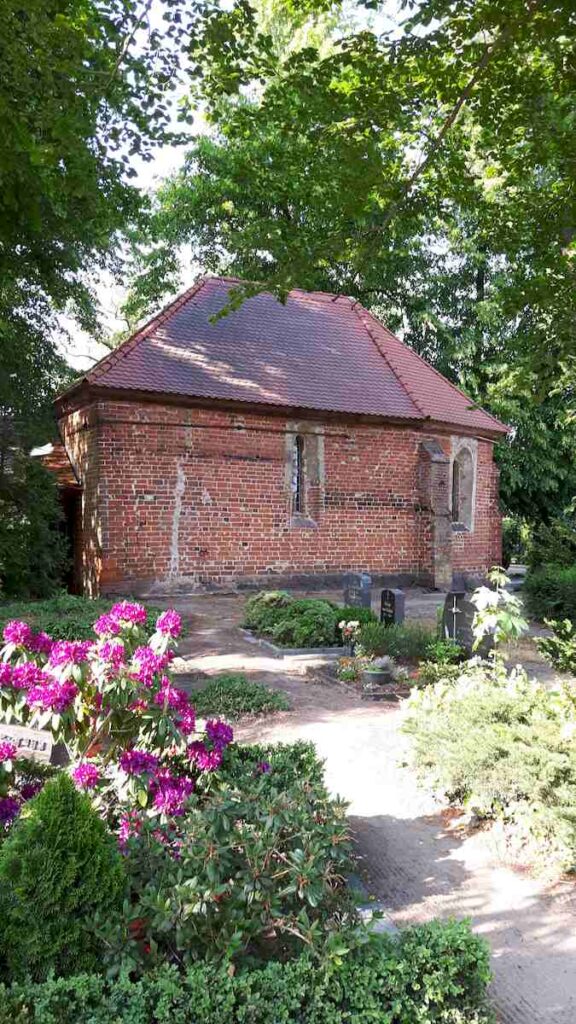

Stephen's Chapel in the Berlin Street Cemetery

The Stephanuskapelle, built in 1351, was a prayer chapel for pilgrims passing through Wusterhausen on their way to Bad Wilsnack. Alongside the town church, the chapel is now the oldest building in the town. Inside there are frescoes depicting images from biblical history.

The chapel is used as a mourning hall and can only be visited on request.

In 1965 the Gothic door on the north side was bricked up and the double-winged gate was added on the west side. In 1991 the roof of the chapel was re-covered and the entrance area was given a roof. In the Middle Ages, it was used by plague victims who, isolated outside the city, awaited death. Mass graves are said to have been near the chapel. After that, the square around St. Stephen's Chapel served as a burial ground for the town's poor.

cemetery

In 1581 the cemetery, which had previously been around the town church, was moved here. Chroniclers speak of an old, pulpit-like linden tree from which sermons were given twice during the week of prayer.

From 1860 to 1870, when a squadron of the 11th and 15th Uhlan regiments were stationed, Catholic services were held here.

The Chapel of St. Stephen – A medieval chapel just outside the city

Text: Dirk Schumann

If the visitor leaves the market square in the direction of Berlin (south), he arrives at the place of the former Berlin city gate behind the crossing with Dombrowskistraße - formerly Holy Spirit Street. The people of Prignitz also called it local patriotically after a nearby place Kampehler Tor (Kampehl is perhaps known to many through the mummy of the knight Kahlbutz shown there). The mill race ran in front of the gate, which was completely demolished in the 19th century. This not only supplied the mills that were still in operation here until the middle of the 20th century, but also served to protect the south-eastern flank of the city in the Middle Ages.

Just behind the former city wall, under shady trees in the cemetery, is the small chapel of St. Stephen.

However, the building used today as a cemetery chapel did not always have this function. The chapel was built on an important traffic axis leading from Wusterhausen. It is probably a street where none of the city's three medieval hospitals were located. Especially in the hospital chapels in front of the city wall, travelers could pause and pray for a good or even successful course of the planned journey or the upcoming section.

The chapel of St. Stephen was probably also intended to serve such a purpose. With the increasing travel activity after the emergence of the pilgrimage site Wilsnack, many such chapels were built outside of towns and villages. However, the history of the St Stephanus chapel in Wusterhausen goes back to a time before the Wilsnack pilgrimage. Because a documentary tradition proves the founding of the chapel in 1351. As Friedrich Adler - the first chronicler and researcher of Brandenburg brick architecture - established as early as 1898, the existing brick building of the chapel can be very well associated with such a founding date. The small single-nave chapel with a three-sided polygonal east end is a building of elegant proportions. Even in Friedrich Adler's time, the chapel had a small portal in the north wall facing the city. However, this was bricked up in 1965 and replaced by a newly created portal in the western wall. Only a few narrow, lancet-shaped window openings illuminate the flat-ceilinged interior. But contrary to the assertion that can be found in the literature that the windows were reduced in size in the 19th century and given their current shape, they come from the original building and are an important indication of the construction period of the church in the middle of the 14th century. Because the medieval wall paintings in the interior refer to the existing window frames.

On the outer wall there are small cup-like indentations in some places. These date back to the Middle Ages and can be found in various churches and chapels, to which special meaning was attached. The attentive observer can also discover them on a buttress of the Wusterhausen town church, which is located next to a portal that was walled up around 1400. Such bowls often appear in combination with grooves near church portals or on sacristies. The production of such bowls is a magical pre-Christian custom that certainly goes back to prehistory. Because you can also find such bowls on Neolithic megalithic tombs or Bronze Age cult sites. However, since there are no written records of this, we have to rely on assumptions today. An answer could be provided by considerations from folklore, which assume that stone dust was taken from holy places, which was then carried with oneself for protection or mixed with food in the event of illness. Folklorists were able to trace some of these practices well into the 19th century.

It can be assumed that the Wusterhausen chapel gained in importance as the flow of pilgrims increased. Perhaps there was even an image of a saint in it that caused miracles, which is ultimately also an important trigger for the pilgrimage. The popular archmartyr Stephen would certainly lend itself to increased worship, as he was very popular throughout the Middle Ages. According to the Bible, Stephen was a deacon (spiritual office) of the early Christian community in Jerusalem. He had to pay for his commitment to Jesus Christ with his life, in which he was stoned by members of the Jerusalem council. That is why Saint Stephen is usually depicted in the image with three stones that refer to his martyrdom.

From the reorganization of church conditions in the course of the Reformation it is known that the chapel of St. Stephen had a lot of small income and even a house, while the Wusterhausen town clerk supervised the chapel.

However, this income does not provide the chapel with any clear indication of its own pilgrimage.

Finally, the chapel was not even completed as planned. For when the chapel began to be built, a vault had been prepared. Not only the buttresses at the three-sided east end speak for it. In the interior, angular vault designs were executed, which, however, ended at the height of the window sill. Apparently, the original planning was abandoned at this point because the money ran out or the building ground did not appear stable enough for a vault.

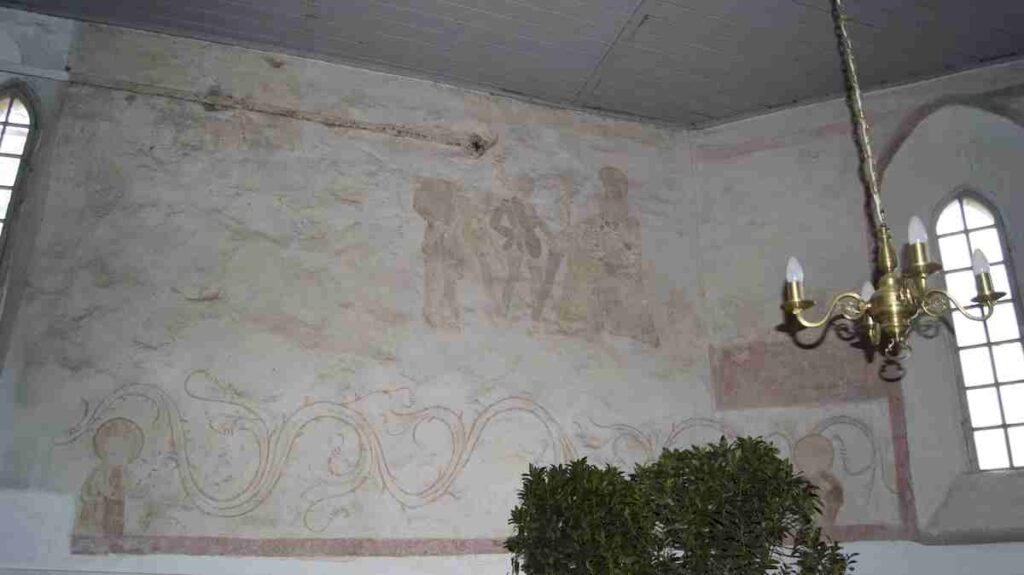

While the exterior of the chapel was originally exposed brick or had a thin layer of paint on which - as was customary at the time - the brickwork was painted on again, there are extensive medieval wall paintings inside. As the local chronicler Karl Altrichter reported in 1888, a mayor had the mural painted over for reasons of cleanliness. Thus, these Catholic medieval paintings could not be seen when the chapel was used as a Catholic place of worship between 1860 and 1878 by soldiers stationed here.

They were later uncovered and restored in 1965. Today, the paintings created in the late 15th century are of great importance for art history because of their almost life-size figures and the gestural way of depicting them, even if they do not embody the highest painterly quality.

The scenes of the wall painting were apparently originally to be read from left to right. The scenes of mocking and the crowning of Christ with thorns can still be clearly seen in the apex of the chapel. The henchmen use long poles to painfully press the crown of thorns onto Christ's head. In the preceding scene of mockery, the contorting henchmen dance eagerly around Christ. Below the scenes are the busts of various saints, whose attributes are barely recognizable.

In their density, the paintings are a reminder that Gothic church interiors were often elaborately and richly painted. This is also shown by the restoration investigations for the Wusterhausen town church. With a few exceptions, however, only modest remains have survived here.

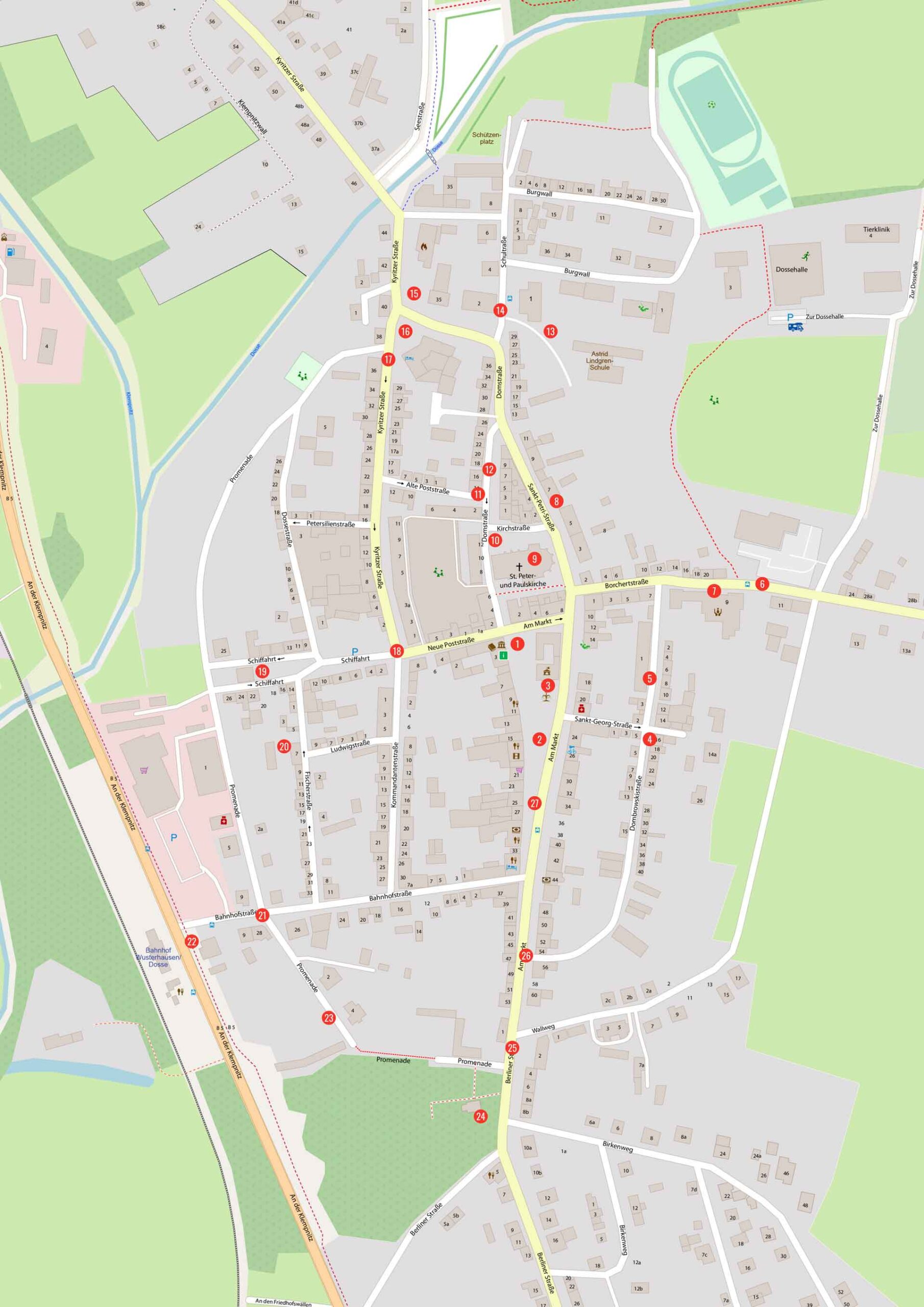

City walk map general view